Statistical physics of signal propagation in deep neural networks

Here I’ve summarized some of the main ideas that underlie the theory of signal propagation in deep neural networks. This theory, which is strongly inspired by the physics of statistical field theory, explains the success of ReLU as an activation function for deep networks and also predicts that the Kaiming initialization scheme is optimal. I wrote this as a final report for a course on critical phenomena in equilibrium and nonequilibrium systems. I hope it’s informative!

Introduction

In machine learning, we are interested in learning patterns in data. In regression problems, we focus on learning a function that uses data (e.g. a digital image) to predict properties of the data (e.g. whether the image contains a cat). To do this, we use a general-purpose function approximator: a neural network. A neural network (NN) parameterizes a family of functions by stacking layers of interleaved affine transformations and element-wise nonlinear transformations. For example,

\[f(\vec{x}) = \boldsymbol{A}^{(L)} \phi \boldsymbol{A}^{(L-1)}\phi\dots \phi \boldsymbol{A}^{(1)} \vec{x}\]where \(f(\vec{x})\) is the NN output on input \(\vec{x}\) and the \(\boldsymbol{A}^{(\ell)}\) are affine transformations each defined by tunable (i.e. trainable) parameters. The index \(\ell\) enumerates the layers, \(L\) is the depth of the neural network, and \(\phi(x_i)\) is a nonlinear scalar function which acts element-wise on a vector. Choosing \(L\) and \(\phi\) is a design decision made a priori. When we train this NN, we tune its affine parameters to search the family of functions for a specific function that well-approximates the true pattern in the data. Training is computationally expensive, so we would like to use theoretical principles to guide design decisions and maximize performance.

Unfortunately, we lack a complete theory that predicts the final performance of a given NN before actually training it. The fundamental difficulty is that neural networks may have billions of parameters whose training dynamics are coupled. This justifies using tools from statistical physics to uncover the basic behaviors and properties of these large-scale systems. In fact, mean field theory, partition functions, replica calculations, phase transitions, and more have become standard in NN theory, reflecting a long history of contributions from statistical physicists to NN theory (Bahri et al. 2020).

In the past decade, practitioners have provided evidence that deeper neural networks a) perform better, but b) are more challenging to optimize. Subsequent work empirically found that a particular choice of \(\phi\) known as ReLU helped alleviate the optimization challenge of deep neural networks (He et al. 2015). All of these observations lacked theoretical explanations for many years. In this report, I will summarize recent results that use statistical field theory to convincingly explain these phenomena.

Field theory of neural networks

In a trained neural network, we expect that two input vectors that are semantically similar (e.g. that both are images of cats) should be pushed towards each other as the input propagates through the network. In this sense, the role of a neural network is to extract semantic structure from the relevant data, which is typically some complicated submanifold in input space (i.e. a ‘typical’ random vector in image space is just noise; we only care about the manifold of ‘natural’ images).

Of course, the way an input is transformed through the network depends on the affine parameters. While the optimization algorithm provides the dynamical equation for the parameters, we must also specify the initial conditions. In practice, affine parameters are initialized i.i.d. Gaussian as

\[W^{(\ell)}_{ij}\sim \mathcal{N}(0, \sigma_w^2/N) \quad\mathrm{and}\quad b^{(\ell)}_i \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \sigma_b^2)\]where \(\boldsymbol{A}^{(\ell)}(\vec{v})=\boldsymbol{W}^{(\ell)}\vec{v}+\vec{b}^{(\ell)}\) and \(N\) is the dimension of the affine input. The parameter variances \(\sigma_b^2\) and \(\sigma_w^2\) must be chosen carefully a priori; He et al. (2015) suggest choosing \(\sigma_w^2=2\), which is now standard due to its empirical success. Now, as in statistical physics, we study the resulting ensemble of neural networks. In particular, we characterize a neural network’s manipulation of the data manifold by studying the inner product between two arbitrary inputs as they are processed layer-by-layer:

\[G_{i}^{(\ell)}(\vec{x}, \vec{x}') := \E{z_i^{(\ell)}(\vec{x}) z_i^{(\ell)}(\vec{x}')}\]where \(\vec{z}^{(\ell)}(x)\) is the output1 of layer \(\ell\) on input \(x\), and \(i\) is a vector component index (dropped later for clarity). The expectation is over the network ensemble. The quantity \(G\) characterizes the changing geometry of the data manifold as it propagates through the network ensemble.

Note that \(G\) is precisely the two-point correlator of layer outputs (Kardar 2007). So, we can restate our goal as characterizing the correlator’s flow from layer to layer. If we want neural networks to preserve important structural information about the input as it flows to deep layers, then we must ensure that the correlator is flow-invariant: in other words, we need to initialize the NN at criticality, so that \(G^{(\ell)}\sim G^{(0)}\) for all \(\ell\). A very deep network initialized far from criticality will yield outputs uncorrelated to the input, and the optimization algorithm will therefore fail (Schoenholz et al. 2016).

However, a major challenge remains. Although the first-layer “field” \(z_i^{(1)}\) is Gaussian-distributed, as \(z_i^{(\ell)}\) flows along increasing \(\ell\), its ensemble distribution increasingly deviates from Gaussianity2. This makes theoretical analysis intractable (Roberts, Yaida, and Hanin 2022). To circumvent this, we take the “infinite-width limit”: we take the dimension of the codomains of all \(\boldsymbol{A}^{(\ell<L)}\) to infinity, so that all the \(\vec{z}^{(\ell<L)}\) are infinite-dimensional. It turns out that ensemble fluctuations of the correlator vanish in this limit. In this mean-field limit, the output fields \(z_i^{(\ell)}\) are zero-mean Gaussian random fields and are thus fully characterized by the correlator \(G^{(\ell)}\).

This field-theoretic framework allows us to theoretically compute the correlator for a variety of choices of \(\phi\), provides a criterion for criticality, and relates these to the geometry of the data manifold and the trainability of the NN.

Criticality analysis

For a NN to be initialized at criticality, we need the correlator to approach a nontrivial fixed point \(\lim_{\ell\to\infty}G^{(\ell)}=G^*\). This will depend on the choice of the nonlinearity \(\phi\) as well as the initial parameter variances \(\sigma_b^2\) and \(\sigma_w^2\). In the infinite-width (mean-field) limit, we obtain the recursive flow relation

\[G^{(\ell+1)}(\vec{x}_+, \vec{x}_-) =\sigma_b^2 + \sigma_w^2\E{\phi(z_+^{(\ell)}) \phi(z_-^{(\ell)})}\]where the expectation is tractable in the mean-field limit since it depends only on \(G^{(\ell)}\).

Roberts, Yaida, and Hanin (2022) use perturbative techniques to compute the fixed point \(G^*\) for nonlinearities obeying \(\phi(\lambda x)=\lambda\phi(x)\), which include the ubiquitous \(\mathrm{ReLU}(x)=\max(0,x)\). By linearizing the flow equation around the degenerate limit where both inputs coincide identically, i.e. \(x_\pm = x_0\pm\frac{1}{2}\delta x\), they find a flow in the correlator perturbation, which can be solved to low order in the perturbation. For \(\mathrm{ReLU}\):

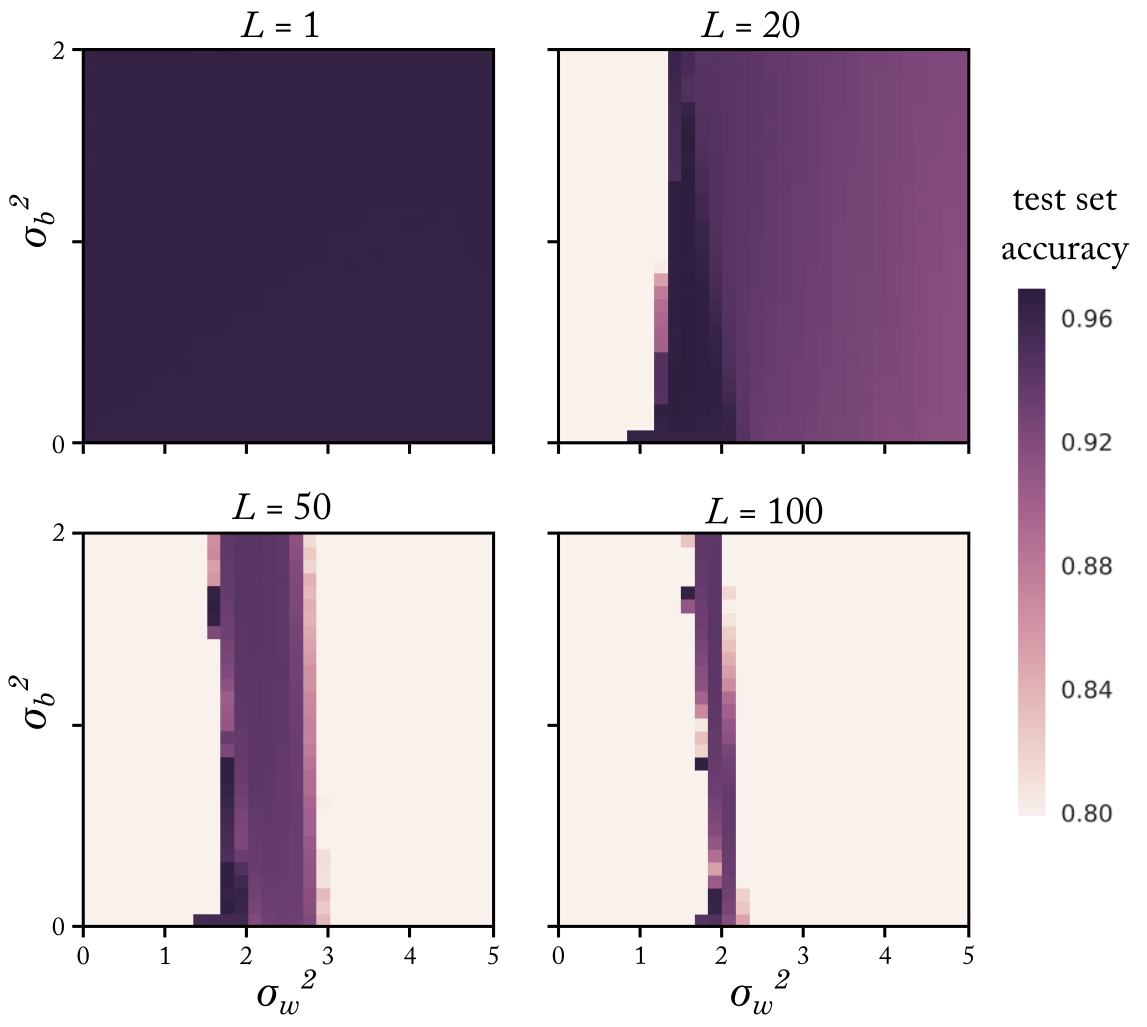

\[(G+\delta G)^{(\ell+1)} = \sigma_b^2+\frac{1}{2}\sigma_w^2(G+\delta G)^{(\ell)}\]which has a fixed point at \((\sigma_b^2, \sigma_w^2)=(0, 2)\). The theory also predicts a semi-critical fixed line at \(\sigma_b^2>0\) and \(\sigma_w^2=2\), where the total correlator increases linearly but the correlator perturbations are at a fixed point. If the NN is initialized on a (semi)critical point, information about the geometric structure of the data can propagate through arbitrarily deep networks without exponentially vanishing or blowing up. As a result, these initialization schemes greatly enhance the trainability of very deep networks, which is exactly what is observed in practice:

We can use this formalism to repeat this calculation for other choices of nonlinearity \(\phi\). The result is that there exists a broad class of \(\phi\) which do not permit a fixed point. Deep networks with these nonlinearities are not trainable. The takeaway is that the theory predicts both the unique success of \(\mathrm{ReLU}\) as well as the Kaiming initialization scheme (\(\sigma^2_w=2\)) which is widely used in practice.

Future directions

Do NNs far from the mean-field limit behave qualitatively differently? Can the field theory framework handle task-specific NN architectures where the affine transforms may have additional structure? Can we go beyond initialization and make quantitative, data-dependent predictions about training dynamics? The field theory formalism presented here is one of many frameworks used to approach the slew of open questions remaining in NN theory. Rapid engineering improvements only deepen the gap between theory and practice; it will take a coherent synthesis of varying perspectives to develop a complete theory of deep learning.

References

- Bahri, Yasaman et al. (2020). “Statistical mechanics of deep learning”. In: Annual Review of Condensed Matter Physics 11.1.

- He, Kaiming et al. (2015). “Delving deep into rectifiers: Surpassing human-level performance on imagenet classification”. In: Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, pp. 1026–1034.

- Kardar, Mehran (2007). Statistical physics of fields. Cambridge University Press.

- Schoenholz, Samuel S et al. (2016). “Deep information propagation”. In: arXiv preprint arXiv:1611.01232.

- Roberts, Daniel A, Sho Yaida, and Boris Hanin (2022). The Principles of Deep Learning Theory: An Effective Theory Approach to Understanding Neural Networks. Cambridge University Press.

- Lee, Jaehoon et al. (2017). “Deep neural networks as gaussian processes”. In: arXiv preprint arXiv:1711.00165.